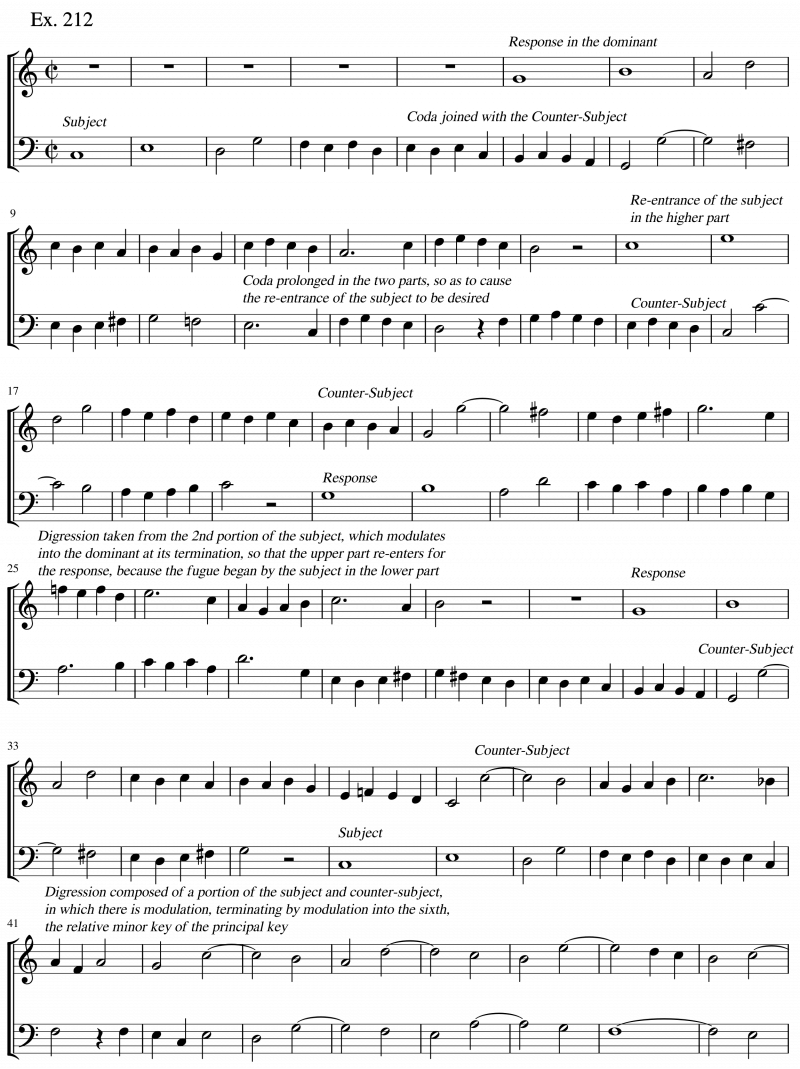

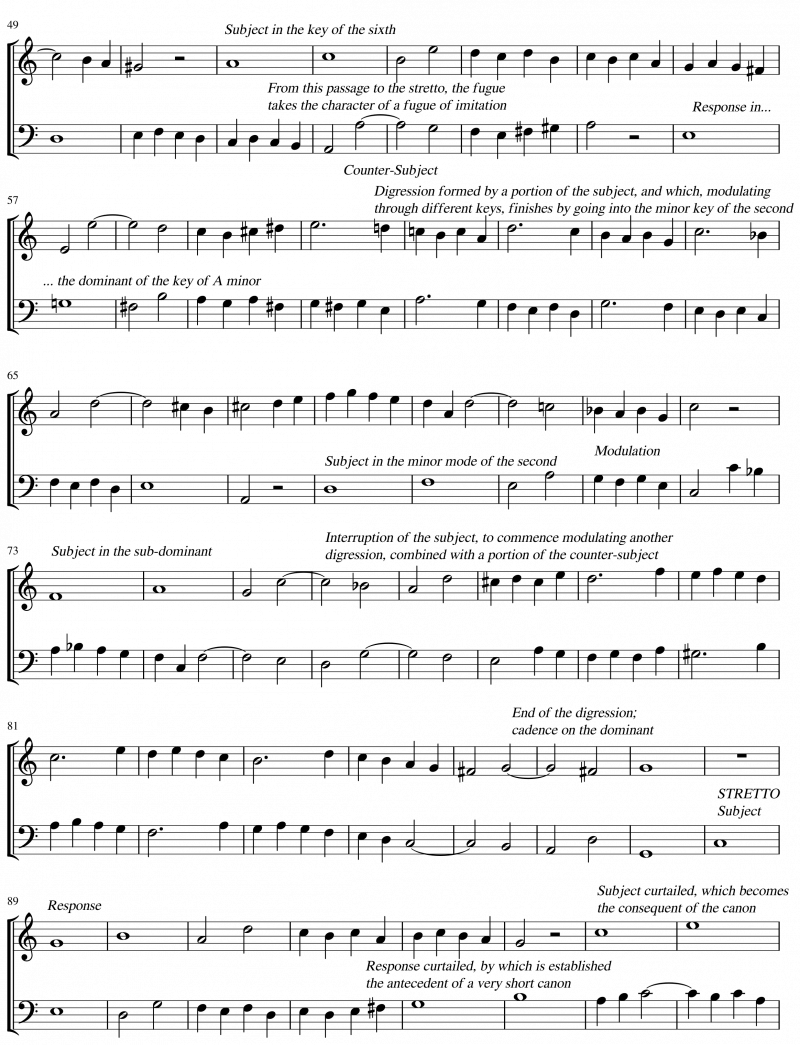

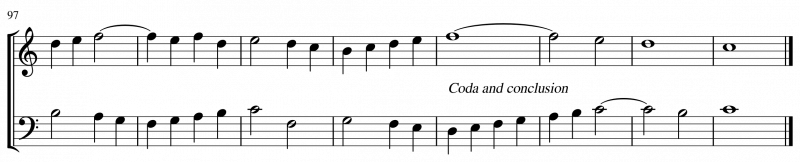

Extended Examples

Real Fugue in Two Parts

General Remarks

On examining the foregoing example, it will be evident that the development of a Fugue is entirely deduced from the Subject, and from the Counter-Subject; it is that which forms the unity of a piece of music of this kind.

As it is necessary to give to each of the parts - whatever be their number - a repose 1), or cessation, in order to vary the effects, these reposes, or cessations, should take place in a part before the passage where the Subject or the Response is to enter. 2) When these cessations are employed under other circumstances, the part which ceases, should never re-enter idly, without reason, or by fillings-up; but it should re-enter, either to respond to some Imitation already proposed, or to propose one in its turn.

It is also particularly recommended, to eschew monotony in the choice of ideas, and in that of the design and phrases; this defeat is blameable in every kind of music; but it is one into which it is easy to fall, in composing a Fugue, if all the ideas forming the whole be derived either from the Subject, or from the Counter-Subject, with a view to the too-strict preservation of that unity in character, above mentioned. In order to avoid this defect, attention must be paid, when planning a Digression, not to employ the same fragments of Subject or Counter-Subject, which were used in the preceeding Digression. With this precaution, and by skilfully varying the modulations, and the aspects of imitations, by inversion, monotony will be avoided.

Another remark that should be made, is, that in a Fugue, whether real or tonal, of which the Response is always in the fifth of the tonic, all the imitations in the course of the Fugue should be made in the same interval as the Response; or in the fourth, which is an inverted fifth.

As to a Fugue of Imitation, if the response is at the fifth, or at the fourth of the Subject, the same law which served as a guide in real and tonal fugues must be observed with regard to imitations; but if the Response be at the second, or at the third, or at the sixth, or at the seventh, or at their compounds, the imitations during the Fugue should always be made at the distance indicated by the Response at the commencement. It may be added, that, the introduction of imitations at the unison and at the octave, is permitted, whatever be the kind of Fugue, and in whatever degree or interval the Response may be.

From these observations, the examples may be continued without necessity for adding anything more to that which has already been said on the subject of Fugue.

Fugue. That which has just been stated with regard to the repose in question aplies to every kind of Fugue, whatever be its number of component parts.