This is an old revision of the document!

Two-Part Counterpoint

Two-part counterpoint is the more strict, both in the ancient and the modern system. The reason for this is plain: the fewer the difficulties to be vanquished, the more the rules must be severe. Two-part writing does not involve so many trammels, as a larger number of parts progressing together; so that the strictness of this kind of composition diminishes in proportion as the number of parts increase.

First Order -- Note Against Note

Rule 1

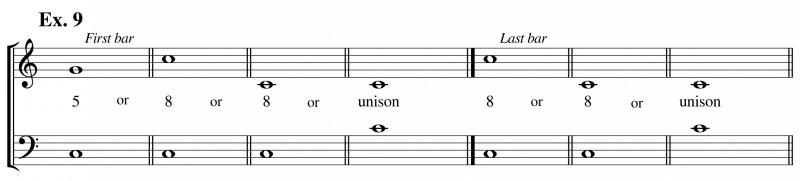

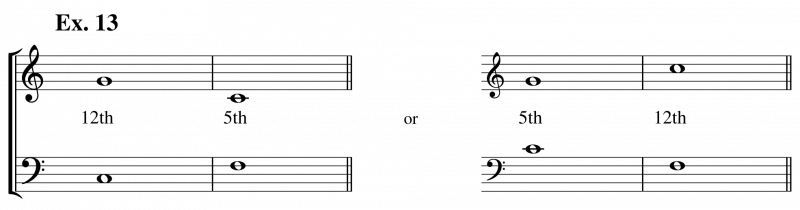

The commencement 1) must be a perfect concord 2), and the termination 3) also, so that the first bar may be either a fifth, an octave (or a unison), and the last bar should be simply an octave (or a unison). Let it be borne in mind, once for all, that by the word “fifth” is also understood the twelfth; and by the word “octave”, the fifteenth, according to the relative distances of the voices employed; and the same will apply to all intervals which may be doubled or tripled.

Rule 2

The parts should progress always by concords 4), with endeavour to avoid the unison, excepting at the first or last bar.

Observation – The principal aim in counterpoint being to produce harmony, unison is forbidden, because it produces none. This does not hold good with regard to the octave; for, although the octave is almost in the same condition with the unison, yet the difference which exists between the grave and acute sound renders it less devoid of harmony than the unison.

Rule 3

It is sometimes admissible to let the higher part pass beneath the lower part, always, however, taking care that they shall be in concord 5), and now allowing this method to continue too long, as it is only admissible in case of extremity, or in order to make the parts flow well, since the pupil should, as we have just said, write for voices:–

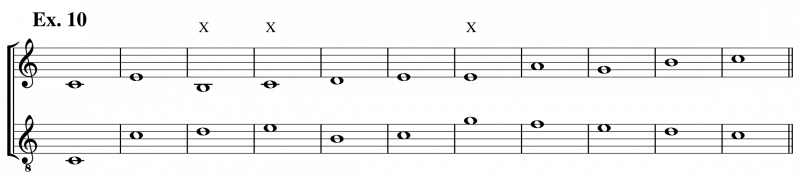

These marks “X” indicate the places where the higher part passes beneath the lower. It cannot, however, too strongly be recommended, that this method should never be employed but with great reserve.

Rule 4

Several perfect concords 6) of the same denomination should never be permitted to succeed each other, at whatever pitch they may occur; consequently, two fifths and two octaves in succession are prohibited.

This prohibition is applicable to every kind of strict composition, in two parts, as well as in more.

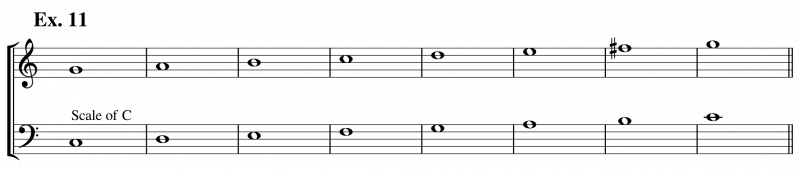

Observation – A succession of octaves renders harmony well-nigh void; a succession of fifths forms a discordance, because the upper part progresses in one key, at the same time that the lower part progresses in another. For example, if, in the key of C, an upper part be added, which gives a perfect fifth at each bar, thus–

Parallel fifths by conjunct motion

It follows, that one part would be in C, while the other would be in G. It is from this concurrence of two keys, that the discordance arises, and consequently, the prohibition to introduce several fifths in succession; as, even when the movement of the parts instead of being conjunct, should be disjunct, the discordance not the less exists.

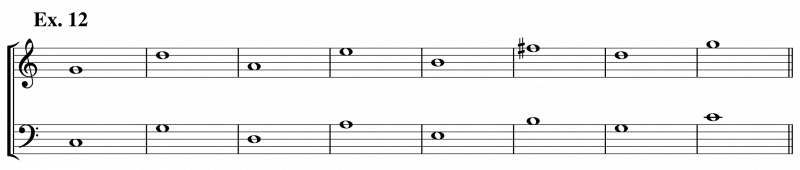

Parallel fifths by disjunct motion

Here is one of these defects arising from “direct movement”, which it was previously promised should be pointed out.

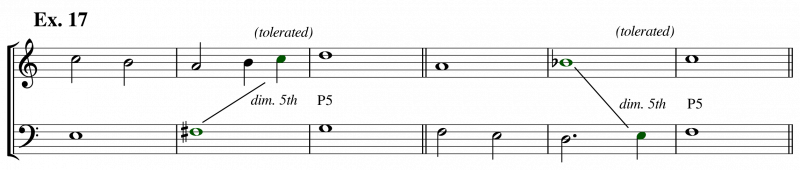

Consecutive 7) fifths have been, and still are, tolerated in “contrary movement”, because if they are of the same kind, this movement causes them to change their nature.

Contrary fifths – Unacceptable in two-part counterpoint

In this example it will be seen that one is a twelfth, and the other a fifth, which changes their nature. Nevertheless, it is forbidden to use this permission in two-part counterpoint, particularly note against note; this method is tolerated in middle parts, when composing for four voices, where there is difficulty in making the parts flow well.

The pupil may meet in works of free composition – as operas, symphonies, etc. – with consecutive 8) fifths; but these licenses are only to be tolerated in this style of composition.

Rule 5

It is prohibited to pass to a perfect concord 9) by direct movement, excepting when one of the two proceeds by semitone 10). This exception is tolerated.

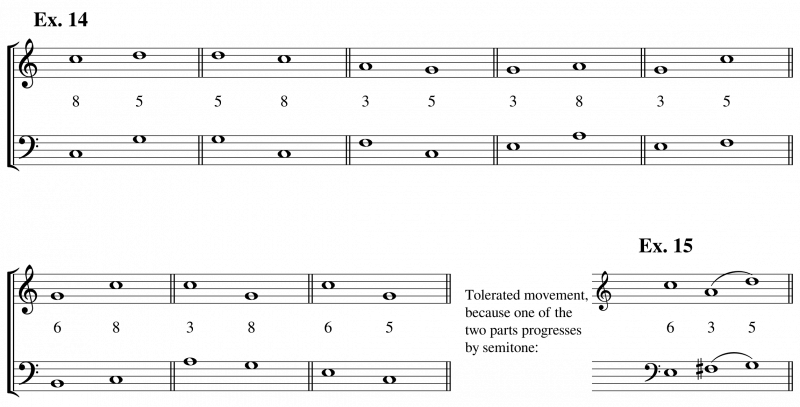

Prohibited movements:

The movements in Example 14 are prohibited, because, supposing the distances formed by the intervals are filled by notes of inferior value ascending or descending, there would be either two fifths or two octaves – called two concealed 11) fifths or octaves:–

Observation – This rule, at first sight, seems ill-founded; because, the intervention of crotchets 12) not being written down by the composer, the two fifths or two octaves do not perceptively exist. But the singer may add these crotchets 13); and in that case, the two fifths or two octaves are clearly heard. The ancient composers, in order to evade the objectionable point which would arise from the inconsiderate license that the singer might take, forbade going to a perfect concord 14) by direct movement. The rule, therefore, to prefer contrary movement, is excellent, because it prevents falling into the defect – hidden though it be – of which direct movement is the cause. This rule, also, indicates yet another objectionable point occasioned by direct movement.

As to the tolerated movement, instanced in Example 15, there the case is different; inasmuch as by filling up with crotchets 15) the spaces marked by the intervals, there result, it is true, two fifths, but one is imperfect, the other perfect. 16)

Example 15 with crotchets

These two fifths are tolerated, because they are not of the same nature, and because the discord 17) of which we have spoken, arising from perfect fifths in succession, does not take place in this ease. The old composers avoided this method in two-part counterpoint; it was only in composition for several voices that they availed themselves of it in one of the middle parts, when they desired to escape from some perplexing point.

Rule 6

All movement should be either diatonic or natural, in regard to melody; and conjunct movement better suits the style of strict counterpoint than disjunct movement. Accordingly, movement of the major and minor second, of the major and minor third, of the perfect fourth, of the perfect fifth, of the minor sixth, and of the octave, are permitted either ascending or descending. The movement of the superfluous 18) fourth, or tritone, of the imperfect fifth, and of the major and minor seventh, are expressly prohibited either ascending or descending.

Observation – This rule is a very wise one; and the ancient masters were all the more judicious in observing it, since they wrote for voices alone, without accompaniment. They thus obtained an easy and correct melody, where prohibited movement would have rendered it difficult of intonation. Nevertheless, this rule has been much deviated from, in modern composition.

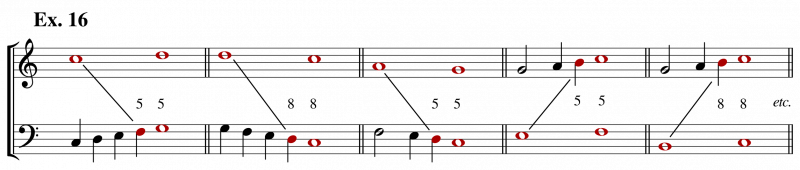

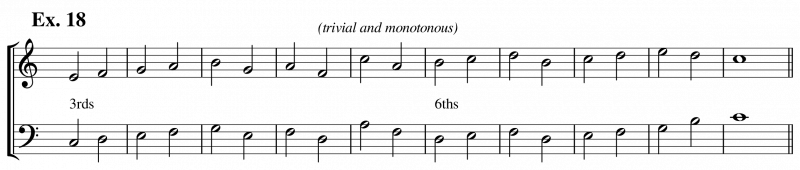

With regard to movement which should be employed in the case of one part respectively with another, it is, as has been already said, contrary movement that should be preferred to oblique movement, and this latter, to direct movement. The last should be very seldom used; for even when all the rules are observed which have been laid down to evade the objectionable point would be incurred – not positively contrary to rule, but contrary to good taste, good style, and the diversity of concords 19); since by this movement, there would be a long succession of either thirds or sixths – producing an effect both trivial and monotonous.

This example offers throughout the same concord 20), the same movement, and consequently the same unvaried effect.

Observation – As many as three thirds, or three sixths in succession, at the utmost, may be used; but to go beyond that number would be a wilful committal of pre-stated error.

Rule 7

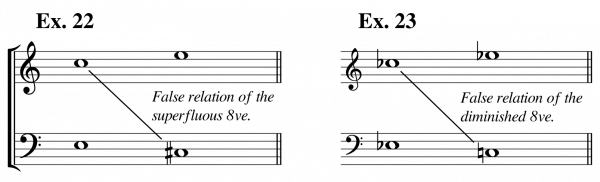

False relation of the octave, and of the tritone, between the parts, should be avoided; these two relations are harsh to the ear, – especially that of the octave.

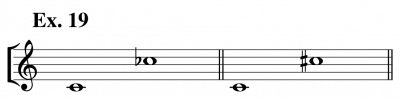

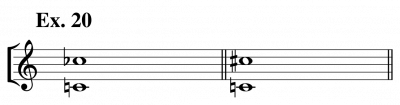

Observation – Relation signifies the immediate affinity existing mutually between two sounds, successive or simultaneous. This affinity is considered according to the nature of the interval formed by the two sounds, so that the relation shall be true when the interval is true; it is false when there is alteration by excess or diminution. Among false relations, those only are included, in harmony, of which the two sounds do not equally belong to the key in which they occur. The diminished octave, or the superfluous 21) octave, is a false relation in melody as in harmony, however they may be used. The disagreeable effect if produces may be mitigated, but not entirely destroyed. The employment of this movement is therefore prohibited in melody:–

False relations of the diminished octave and the augmented octave

In harmony, the use of these octaves struck simultaneously, and held down for some time, is inadmissible.

Nevertheless, there are modern composers who have thought fit to employ it, thus:–

In this case they consider the C-flat and the C-sharp but as passing alterations, and as notes of little value struck in the unaccented part of the bar.

It it a very great license, which is only just to be tolerated in a style of composition of the freest kind, but which should be rejected altogether in strict counterpoint. There exists another case, in which the false relation of the octave in harmony may be hazarded, between two different chords, as thus:–